IntroductionMOGADISHU, SOMALIA

1990

The year is 1990. The air is thick with the putrid smell of burning tires, and the crack of gunfire echoes in the distance. I am four years old, and the city of my childhood is no longer a bustling and burgeoning metropolis but a vacant and violent war zone. Gone are the weekends my family would spend together along the coastline when I would play with my awoowe (grandfather) in the grainy sand. No longer do the nights of gathering to sip tea exist. Instead, we’re living in constant fear and uncertainty. Many families like mine are strategizing on how to flee the country as it teeters on the brink of nothingness.

NAIROBI, KENYA

1991

By 1991, the fighting had escalated to total civil war and an entire collapse of the state. My hooyo (mother) has taken us, her four children and nine months pregnant with her fifth, across the Kenyan border to the UN refugee camp.

I am five years old, and we are living in the Dadaab refugee camp. My siblings and I spend our days running around the tents while our mother sets up a goods store. She stocks it with rice, flour, beans, and cooking oil as well as canned goods and other packaged food items, and we help her unpack the boxes and line the shelves each day.

Our fellow camp mates come into the store. They ask her for rice, pasta, and clean water and for daily updates about Mogadishu. Despite these difficulties, we are a vibrant community, united by the experience of displacement and the search for safety and security. While our camp residents face significant challenges, they are also a testament to the resilience and strength of the human spirit in the face of adversity. This is when I learn what grace looks like.

SEATTLE, WASHINGTON

1993

When I’m seven, my mother decides that I should move to Seattle to live with a family friend. “You will have more opportunities,” she tells me in our apartment in Nairobi, a place she was able to afford to rent with the money from her goods store. Though I am her second eldest child, I am still too young to disagree with her.

My family waves as I board the flight from Nairobi to New York. From there I will fly to Seattle. In my new home, snow is falling all around me in soft, wet flakes. They carpet the streets and land on my cheek, like a gentle kiss. It’s silly, but the snow feels like a promise: my life will now be completely different from my one before, far from the uncertainty and constant fighting.

I start school at Tops Elementary, join the basketball team, and learn English. I’m excited, but soon I feel a deep sense of homesickness. I miss cooking canjeero, bariis, and pasta with my mother. I long to boss my young siblings around again. My big new world seems like an empty dream. I feel angry at everything around me. I can’t believe I’m supposed to start over alone.

My mother calls often, and we have pep talks about things I should expect from people or how to get things done. I feel prepared at a very young age. My mother was brave and strong, and I knew I had to be, too. I throw myself into my new world, surrounding myself with people who share my drive and determination.

OSLO, NORWAY

2008

Fifteen years after moving to America, I finally reunite with my hooyo and siblings. Unable to receive their travel documents to join me, they stayed an extra seven years in Kenya before relocating to Oslo.

In the intervening years, my mother has remarried and had five more children, bringing my total number of siblings to nine. She has opened a furniture store and a Somali goods store. She primarily sells traditional Somali clothing and accessories, such as dresses, headscarves, and jewelry. Meanwhile, I have been discovered by a modeling scout while attending college in Seattle. I will go on to live in New York City for nearly two decades and travel the world.

OSLO, NORWAY

2014

I return to Oslo from New York looking for myself, wanting to reconnect the dots of my life. It is the first time I’ve lived with my mother since I was seven years old, and I’m right back there again as my little-girl self. There’s tension between us because she wants me to be that small child and I’m a fully actualized adult with a career and a life. Bubbling up to the surface that hot summer is the clarity of abandonment I’ve felt over the past twenty-one years, as though I’d been left and forgotten. I realize then that I can’t have been the only one who’s been on that winding road of displacement. But why don’t I know others who’ve traveled similar paths? Where are our stories? This is the moment I know I will tell these big stories, and I will tell them through food, which is a perfect Trojan horse and a welcoming gateway into culture. Food is both a record of the upheaval of wartime and a comforting talisman of where you’ve come from and who you are. It’s the tie that binds you to your people wherever they are in the world.

BROOKLYN, NEW YORK

2023

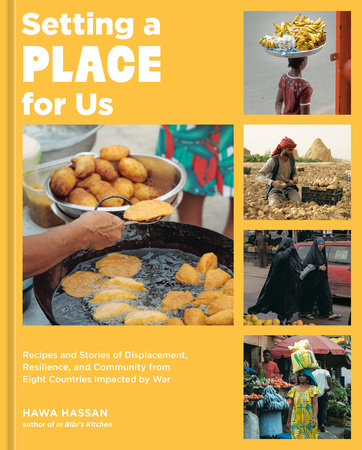

I’ve spent the last year traveling across the world to document stories and collect recipes. It will have taken a decade for me to realize the vision I had on that revelatory trip to Norway. In those ten years, the world has witnessed only more violence and strife. People are still living in wartime conditions, and as my family did all those years ago, they’re still leaving their homes and crossing borders. Through it all, they continue to hold their families, friends, and memories together with food.

That’s why this book exists: to show you how we who experience violent or invasive conflict in our communities and daily lives are more than our travails. We are who we choose to be no matter what life throws at us. As Warsan Shire, the Somali British poet, says, “No one leaves home unless home is the mouth of a shark.” Time and time again, I have seen and experienced that when people live in the mouth of the shark, when blood is in the water, what ultimately surfaces is gratitude, family, community, connection, and togetherness. And it’s usually expressed through food or a meal of some kind.

When I first embarked on this book, my intention was to visit all eight featured countries— Afghanistan, Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, El Salvador, Iraq, Lebanon, Liberia, and Yemen—to conduct interviews, sample local cuisine, and delve into how these nations preserve their cultural heritage through food and recipes. Sadly, due to the pandemic and safety concerns, I was unable to travel to all the countries included in the book.

The eight countries I focus on not only boast diverse cultures, histories, and cuisines, but they also share some commonalities. One of the most significant is the impact of historical events such as wars, colonialism, and geopolitical conflicts, which have left an indelible mark on their societies and culinary traditions. I selected these countries because, much like my beloved Somalia, they have also grappled with ongoing unrest.

Drawing from my own experiences as a refugee and a displaced person, I aim to explore these countries not only to document the obvious, but also to examine the subtle nuances that inherently bind us together. From the simple joys of everyday life to the rituals of setting the dinner table and the connections often forged over a shared meal, I seek to uncover the common threads that unite us all.

Copyright © 2025 by Hawa Hassan. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.