Chapter 1

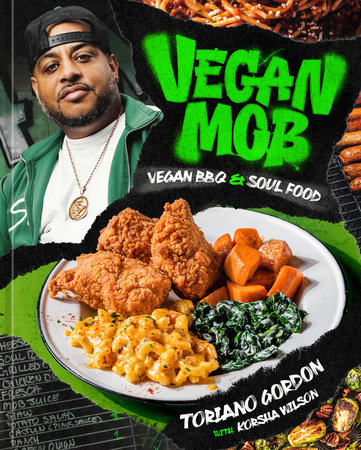

Since I opened Vegan Mob in 2019, the Oakland community has really embraced me and my version of comfort food. The base of the menu may be American classics, but the flavors blend influences from a lot of the cultures you see here in the city. I use ingredients and techniques from my family’s classic soul food recipes, as well as Asian, Latin, and Caribbean cooking to create Vegan Mob’s plantbased dishes, because those communities have impacted this area, and those ingredients are readily available to me here. In the Vegan Mob kitchen, I experiment with plant-based ingredients, remixing them to create meat-free versions of dishes from those cultures, creating food that is big on flavor—and I don’t stop remixing until I get it just right.

Part of the reason why I think Vegan Mob has been received so well by the neighborhood and customers is because the restaurant also reflects me, and I’m a product of the Bay Area. Vegan Mob and my music are the results of a lifelong love of all things creative, but the restaurant is also the result of Fillmoe, otherwise known by those who are not from the neighborhood as Fillmore, the neighborhood that raised me and gave me my swag, that taught me the importance of community while also instilling in me the importance of keeping it real and being true to myself.

Fillmoe is a neighborhood in northeast San Francisco about a dozen miles away from my restaurant, across the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge. In the 1950s Fillmoe was known as the Harlem of the West, a place that was hella Black, with Black music, Black art, and Black food. Artists like Billie Holiday, John Coltrane, and Dizzy Gillespie all came through Fillmoe on their tours of the West Coast to perform for Black crowds at local spots like New Orleans Swing Club. Black nightclubs lined Fillmoe and Post streets, giving folks the chance to hang out with one another until the wee hours of the morning, listening to live music and having a drink. They were bringing the sounds of their homes on the East Coast or in the South with them to the West Coast, creating a community that resembled where they were from. If you really think about it, Fillmoe was where folks moved for jobs and opportunity, but underneath was homesick Black folks who built what they knew in their new spot.

When I was growing up, Fillmoe was a Black neighborhood and San Francisco felt like a Black city. Black businesses were everywhere in Fillmoe—Marcus Books, Mrs. Dewson’s Hats, and the numerous bars and restaurants that lined Fillmore Street, all of them Black-owned. My favorite record shop was called Mo Music for the People; it was owned by a Black entrepreneur who went by Showtime. Showtime is my mom’s longtime friend, and I called him Uncle. Mo Music for the People was a hub for us growing up; they sold all the new CDs, incense, posters, and even clothes. My friends and I stopped by every Tuesday to buy new hip-hop albums. When I recorded my first album, I wanted to buy a fake Versace shirt from the store to wear on my album’s cover photo, but I couldn’t afford it because it cost $300. So, I went and talked to Showtime. He said if I swept up his shop for a couple weeks, he would let me have a shirt. That was that—we had a deal. I learned a lot from Showtime, and he set an example for many of us growing up.

Seeing Black people own their own spaces made us kids in the Fillmoe feel like we were surrounded by greatness. It made us believe that we were and could be great, too. It was inspiring. It also made the neighborhood feel like a big family. We all looked out for one another as we grew up.

When gentrification pushed Black people out of San Francisco, the change to Fillmoe was quick—so quick that it almost makes me forget how it used to be. A lot of Black people from San Francisco have moved to Oakland and other Bay Area cities. Walking through the neighborhood now, you can see remnants of what it used to be like, but a lot of it is gone. Oakland now feels like how Fillmoe used to: a Black mecca of the West, where we can still tell our stories and own our own spaces.

The Fillmoe had (and still has) its own swag that will always infuse everything that we do, and it inspires music from around the Bay. We have a lot of confidence and a lot of talent, and I carry that in myself and in my music. Our culture here has influenced music worldwide. R&B legends such as Tony! Toni! Toné! and En Vogue, and rap legends like Too $hort and E-40, are just a few of many iconic musicians from the Bay Area. Bay Area musical history and tradition has created and will create generations of talented musicians going forward.

I use music in the same way I use food—to express myself and tell my story. Music has always been one of my main loves, and I always knew I wanted to be a rapper. As a teenager, I wrote rhymes about hustling and being a player, hanging out at the park, and tagging buses. I sold mixtapes out of my school locker. Hip-hop informed my life at that point, taught me to keep it real with everything I did. Soon, I was recording my first album with Done Deal Records, with plans to go nationwide. I felt like I was doing something really big. My mom was tripping; she didn’t want me to sign a contract, miss school, or drop out. But I still went to the recording studio three days a week after school to record my music. My love of making music emerged during those times.

When I was eighteen and old enough to sign my own contracts, I started putting out my music officially. I was in a group called Fully Loaded with Big Rich and Bailey, two West Coast rap legends. Being in the studio with them and legends like Messy Marv, one the most influential gangsta rappers in the Bay Area, showed me how to keep up my skills. One time I was in the studio with the Fully Loaded crew and Messy Marv. We had been chilling, so everyone was lit. Marv was slumped over in his chair dead asleep. We had to shake him awake to go into the booth to record his verse. He jumped up and did the most fire verse I’ve ever heard in my life. We were like, “Man, this boy is crazy.” Seeing rappers like San Quinn also helped shape me and taught me to get up, knock out what I’m doing, and bring style to everything I do. Just like you can tell when a rapper is from Harlem from the sound, you can tell when a rapper is from Fillmoe.

Even to this day, my food—everything I do—is hip-hop. Remixing dishes, making them vegan, and blending influences to make a new recipe requires me to be creative in the kitchen just like I’m creative on the mic. When I’m in the kitchen, I’m expressing myself. Just as those music skills rubbed off on me, learning from my family and being in the Bay really,

really rubbed off on me in terms of food. With food and music, the Bay is a mixture of influences coming together to create something unique.

Almost five years ago, I decided to go vegan because I wanted to be healthier. I had caught the flu, and it felt like it wasn’t going anywhere. I wasn’t getting better, and I was also scared because people were dying from pneumonia. A friend of a friend—another parent who had a child in my daughter’s soccer group—died from it. After that I started juicing and drinking hella ginger shots. Then I decided I didn’t want to eat meat anymore, and after that I cut out dairy. I stopped cold turkey to kick the flu, basically, and so I could be healthier to invest in my future. I wanted to be around for my kids and their kids. When I cut out meat, I found that I had more energy, and my emotional state was better, too. I was more positive. It was enough to encourage me to make a long-term change. But I had no idea that eating this way would lead me down a whole different career path. Today I feel better than ever.

But being vegan, I missed the things that I grew up eating, like soul food and barbecue. I really love barbecue. It’s one of my favorite things to eat and I hated the idea of never having it again. When I was growing up, my uncle “Bobby Joe” from Texas showed me how to make barbecue at home because, as he put it, “San Francisco don’t know nothing about no barbecue.” Years after he passed, when I decided to open a restaurant I thought, “Why don’t I try making barbecue without meat? I’m gonna show him and everyone else how we make this barbecue vegan style.” I didn’t know exactly where to begin, but I just started with what I knew: macaroni and cheese, fried chicken, and brisket. I started simple, just smoking and grilling plantbased proteins at home, making sauces, and testing recipes until they started to feel right. I looked for vegan substitutes, especially for vegan proteins that hit just like the originals, and thought long and hard about how I could make substitutions that would keep the same flavor, the same soul, just without the meat.

Copyright © 2024 by Toriano Gordon with Korsha Wilson. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.