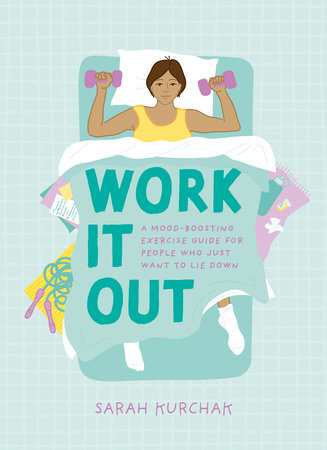

Introduction

“Have you tried exercise?”

If you’ve ever had less than 100 percent perfect mental health, there is a very good chance that some well-meaning person has said this to you. There’s an even better chance that some smug and not so well-meaning types have said it, too.

I’m going to take a wild guess and assume that this terribly helpful advice did not fix you.

The problem isn’t exercise. It is true, unfortunately, that any physical activity done with any regularity has the potential to improve your mood. It’s not a miracle cure or an all-purpose substitute for other interventions—you should not, under any circumstances, drop everything else you’ve been doing to take care of yourself and give me twenty. But exercise can provide focus, routine, comfort, and even a boost to physical health when it feels like everything else is going to hell. And yes, it can make you feel less like shit.

During the ten years I worked in the fitness industry, I saw a number of clients who had depression and anxiety, and I witnessed the positive influence that our workouts had on their lives. I’ve also felt the mental benefits of physical movement for myself. I’m not a fan of big, sweeping statements about the power of fitness. I find that kind of overly plucky talk grating and alienating. But it’s fair to say that discovering workouts that I enjoyed and regularly doing them has played a part in keeping me alive. And I’m not talking about their effect on my cardiovascular system.

Exercise can help people who are dealing with anxiety and depression. But telling them that exercise can help? That’s one of the most useless things in the history of fitness. And the history of fitness has given us homeopathic sports supplements, ab-toning belts, magic seaweed yoga pants, and kettlebell routines for stationary bikes.

“Have you tried exercise?” (or, perhaps even more inescapable, “Have you tried yoga?”) is annoying and insulting. Of course you’ve tried exercise! It’s not new. Its ability to boost mental well-being was not obscure or privileged information that had never been imparted to you before some rando decided that the best response to your struggles was, in essence, “Bummer, try jogging that off.”

It also completely fails to understand the crux of the issue. Most people who are dealing with conditions like anxiety and depression are already aware—often too aware—of the things we could or should be doing to make our lives better or more manageable. But knowing what you should do, or even what you want to do, and not being able to do it is kind of a big part of the whole being anxious and depressed thing.

When I started researching the topic for my clients and myself, I noticed that most of the accessible articles and information involving exercise and mental health fell into that same trap. The fitness industry is filled with lifehacks for depression, but most of it seems to be coming from a place of ignorance about the cold war going on in the average depressed person’s head. The introductions talk about how great exercise is for you, and then they jump straight to tips on motivation, routine, and the physical activity itself. Those tips aren’t necessarily wrong, but when you’re suffering, they’re not realistic.

Moving our bodies within their capabilities is a fundamental part of life. It can be a source of physical and mental well-being. It should be a source of joy. But so much of the information about how you can do it and the venues to do it in is patrolled by a culture that prefers competition, punishment, and shame. There’s clearly a huge need for exercise research, programming, and resources that understand depression. But there’s also a need for resources that appreciate how alienated so many people feel from fitness culture—and, indeed, from their own bodies as a result of fitness culture. And there’s a desperate need for people with any authority in that realm to acknowledge how hard it is for so many of us to just try exercise, especially when people are already working so hard to stay alive.

With this book, I have an opportunity to do my small part to answer those needs. I’ve included practical tips for how to find physical activities that you don’t hate, how to integrate them into your life, and how to do them safely. I also talk about how and why exercise can help you, how and why it often ends up hurting you instead, and what you can do to try to break that cycle. And I’ve woven a bunch of validation and encouragement throughout. If you’ve ever needed an outside source to confirm that getting into exercise isn’t easy, that the fitness industry is kind of full of it, and that you’re doing your best, it’s all there for you. From a former fitness professional, no less, if that helps you take it to heart or gets some judgmental dick off your case.

I’ve written with a focus on people with depression and anxiety, because that’s what I have the most experience with and that’s the population I feel most assured addressing directly. But I believe there is plenty of material here that can be useful to any neurodivergent person. Or anyone who is just a little sad, for that matter.

My goal is to help you feel better, so I’ve eliminated the aspects of fitness that only make people feel worse. There’s nothing about diets in here. On a professional level, I’m unqualified to give advice. On a personal note, I hate them. There’s definitely nothing about weight loss. The only time I’ll discuss weight at all is to acknowledge how abusive and unscientific fatphobia is.

There are other absences from the book that are less righteous, though. The big one, for me, is modifications. I am a huge fan, and I discuss them in a general sense. I encourage you to adapt exercise moves to meet your body’s needs instead of the other way around. I remind you that modifying exercises is not cheating and even so-called easy versions can offer new challenges and results. But I don’t have the space to include every adaptation for every ability level and for every disability that the trainer in me would love to. You’ll have to bring awareness of what your body can and can’t do—but what you have from me is blanket permission to skip anything that feels bad in a way that never winds up feeling good. (Or to skip exercise entirely, if its negative effect on your body is worse than its positive effect on your mind. For instance, exercise may be harmful for people with injuries or chronic conditions. If that’s you, check in with your body and your doctor before listening

to some book!)

Space and scope also limit how geeky I can get about workout plans. I do share basic training ideas and exercises for strength, cardio, and mind-body work, but I don’t provide detailed routines. However, I do offer guidance on how to develop your own plans from a menu of options (see the chart on pages 10–11). If you’re depressed and looking for tips on how to get into exercising and find the perfect workout for developing stability and mobility in the shoulder girdle, for example, this isn’t the only resource you’ll need. Consider it the warm-up portion of your journey.

If a lot of words are beneficial to your learning and processing styles and you have the mental energy to tackle a whole book, or a whole chapter, you can read this book straight through like you would any other book. If you’re running low on energy but could use some suggestions and maybe use a nonperky pep talk or two, you can scan through to find the sidebars and infographics. And if you just want someone to tell you what to do, follow the charts.

And however you use this book, please take the information that works for you and discard the rest. I’m here to help, not dictate. (Although if you would rather be told exactly what to do, there’s something here for you, too.) The last thing you need is one more a-hole telling you what you should do.

Copyright © 2023 by Sarah Kurchak. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.