INTRODUCTIONGrowing up in Kingston, Jamaica, my earliest memories all involve food. One of my fondest memories from childhood is that feeling of looking forward to the weekend—not because I would get to sleep in, watch cartoons, or eat ackee and salted cod on Saturday morning (although I did love that!), but because of Friday night. I knew on Friday night I would attend church service, and on the way home, when it was late, and we were all hungry, we would drive past the jerk chicken vendors. The smell of the spices and the smoke wafting, the sound of the music, and the sight of people gathering to eat—all dressed up before going out for the night—is ingrained in my brain, and jerk has been a fundamental part of my evolution as a chef.

Cooking was a family thing for us. My dad’s mom ran a cookshop—a small, casual, almost take-out style restaurant—and my mom’s mom was the go-to cook for everyone in our family, and the whole neighborhood, really. She didn’t have any formal culinary training, but she was always being asked to cook for church gatherings, birthday parties, and all kinds of events. With two grandmothers who were great cooks, I came to understand the basics of cooking early on. But it was my mom’s mom who taught me the most. She was the type of cook who understood food in the most fundamental way. She didn’t need a recipe, a timer, or a thermometer, because she knew intuitively how to get things just right. I swear you could taste the love in her cooking. She was a machine in the kitchen—every movement was made with efficiency—but she was also natural and relaxed, and we had

fun. In her kitchen, the music was always blasting. I loved to hang out with her there. It put me in such a zen mood. Now, whether I’m making a recipe I know by heart or preparing the most complicated tasting menu, I always feel positive and relaxed when I’m cooking, and I know that’s down to her.

My grandma started me off with simple tasks, like peeling garlic, chopping onions, and boiling and peeling eggs—and I asked

a lot of questions. On Sundays, my job in the kitchen was to clean, tenderize, and season whatever choice of meat that was for dinner. This was a huge responsibility and I had to make sure it was perfect. Saturdays were synonymous with soup—Soup Saturday as it’s known in Jamaica. The soup of the week depended on what was available at the shop (the local grocery store) and whatever ingredients we had leftover from dinners during the week. I was tasked to go shopping for the protein. My uncle would give me $250 Jamaican and tell me to “buy a pound of flour and get whatever meat you can with whatever left back.” I would generally opt for chicken feet; they are my favorite, and were the most inexpensive, so I could buy tons to go around (the more premium proteins, like snapper or chuck, didn’t fit the budget we were working with!). As I was heading out the door, my aunts and uncles would be getting the base of the soup ready: carrots, onions, scallions, and a bit of Scotch bonnet, plus a package or two of Grace Cock Soup (a bouillon powder of concentrated vegetable seasoning, and tiny shards of noodles). Then we’d add in different ground provisions depending on the protein in the soup, and what was in season. Chicken and beef soups would usually include yellow yam, Jamaican sweet potato, cassava, corn, sometimes plantains, and always spinners (flour dumplings); the seafood versions had many of the same, usually with chayote or okra in the mix too.

When I was about 15 or 16, I moved from Kingston to Long Island, New York. My mother had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and wanted to give me a better chance of succeeding, so she sent me to live with her mom, who had recently moved to New York. Those years were the most formative of my life—I learned so much about myself while living under my grandmother’s roof. It’s where I truly discovered my passion and love for cooking, and where I began a relationship with God. Nothing made me happier than helping my grandmother in the kitchen. She wasn’t cooking for a living anymore, but putting in long hours as a personal support worker, so I always tried to have a nice meal waiting for her when she got home. I didn’t have any real interest in playing video games or sports, going to the movies, or talking to girls as a teenager—it was all about cooking. And with my grandmother as my guide, I learned a lot about the possibilities cooking offers. I learned that food not only nourishes me, but it is the best way I know how to express myself to the world. It’s what makes me happy and is a huge part of what defines me as a person.

I’ll be forever grateful to my grandmother for introducing me to what would become my career. I wouldn’t be the man I am today if I wasn’t a chef, and if she hadn’t instilled the drive and ambition I needed to make it in this industry—through culinary school at George Brown College in Toronto, my first few formative years out of school, and the ups and downs of opening several businesses. As I came up in the food industry, I didn’t see many Black chefs at the helms of restaurants. A huge motivator for me has been to increase the representation of Black chefs and the cuisines those chefs could represent. With my passion and my love of cooking, I realized that I could do this: I could be one of those chefs who helped open the door for more people like me, and together, supporting each other, we could celebrate our food and bring it to the forefront.

AFRO-CARIBBEAN COOKING

I pride myself on weaving all the different influences of my life into my recipes, but my Jamaican upbringing has inspired me the most, hands down. That’s something I’ve come back to in recent years—after years of relying on the French techniques I was taught in culinary school, and using butter and cream at every turn, I’ve turned back to my Afro-Caribbean roots, both in ingredients and techniques. In honing my identity as an Afro-Caribbean chef, I’ve been exploring more about thelinks between the flavors, ingredients, and ways of cooking you’ll find in the Caribbean, and those of the African continent. I’m still scratching the surface of what I know will be a lifetime of learning, but what’s clear to me is much of how and what we cook in the Caribbean was brought to the islands by enslaved people hundreds of years ago. From the ancestral ingredients brought over on the ships in the form of seeds, to the cooking techniques and recipes passed down orally from one generation to the next. To me, actively exploring the history of the food I’ve grown up with, and connecting the dots for where the ingredients I cook with originated, or how the dishes I make have evolved, is a mark of respect to my ancestors. It educates me as a chef, and means I can pass on this knowledge to the next generation.

As respectful as I am of tradition, I don’t always stick to the classic way of cooking Afro-Caribbean food. Often, I’ve found there

isn’t one right way—through conversations with family, friends, and fellow chefs (“You put coconut milk in your curry goat?”), I’ve realized that different cooks and communities have their own way of doing things in the kitchen. Truthfully, I also don’t want to limit myself as a chef. I’m constantly inspired by new ingredients and different techniques and cuisines— people I meet, places I travel, and food I taste—and love incorporating that into new dishes and ideas. Although I often start with a version of a traditional recipe as my base, I’m always giving food my own spin, and that’s what you’ll find in this book. Likewise, there are Afro-Caribbean dishes you might be familiar with that you won’t find a recipe for here— things like Jamaican patties (although you will find my spin, Jamaican Tourtières, on page 80), or johnnycakes or festival, which are heavier dishes than I generally eat. These are dishes that I know are popular, but if I don’t feel like I can give you a new or different take on them, I’d rather give you something completely fresh instead.

The Jamaican motto is “out of many, one people,” and there are so many different backgrounds on the island that have all come together to create the most delicious food traditions. Indo-Caribbean and Chinese- Caribbean cuisines, in particular, have had a big influence on my cooking—because I enjoy them so much, I want to build those flavors into my food!—as have Afro-Caribbean cooking from other Caribbean islands beyond Jamaica. Incorporating ideas from another cuisine into your own can be a way of showing genuine admiration for it—as long as you respectfully do the research first, and put in the time. Recently, I was developing a Trinidadian Doubles recipe for a restaurant project I’m working on, and it took me on a months-long journey to rest assured I was doing it justice. My restaurant partner, who is Trinidadian, said they weren’t tasting right—although they were tasting good, they weren’t what he remembered from back home. The issue, it turned out, was in my flour: I was missing the lentil flour traditionally used in Doubles. Lentil flour isn’t easy to get hold of outside of Trinidad and Tobago, so I ultimately ended up going with a mix of two flours—chickpea and all-purpose—that gave me a dish I was proud of for the restaurant, while still respecting the originating culture.

The recipes in this cookbook come from a life spent cooking, experi- menting, learning, testing, reading, researching, and then cooking some more. They are the culmination of my experiences and reflect who I am, where I come from, and how I grew along the way. Every recipe in this book has a story behind it—whether it’s from peeling potatoes in my grandmother’s kitchen, bringing jerk chicken to Toronto’s Little Italy (I liked to say the only thing missing was the sand), prepping hundreds of pounds of wings in a basement under a basketball arena, running a food truck without a license (but with chicken so good, the police told me how to break the law to keep it going!), or a conversation with my fellow chefs about bringing an ancestral ingredient into the spotlight— these recipes reflect what inspires me, how I like to cook, and—most importantly—what I like to eat!

With this cookbook, I hope to inspire you to cook and eat more Afro-Caribbean cuisine, and to help bring an increased appreciation and respect for it, too. I’m a huge champion for being adventurous in the kitchen, and there should be nothing holding you back from jumping into these recipes. I’m all about making food that people just

really want to eat, because it’s so damn tasty! For me, there is nothing nearly as satisfying as serving someone a heaping plate of food bursting with color and flavor, and seeing them enjoy every last bite. That’s what I hope I can bring you with this book—tasty, modern, Afro-Caribbean comfort food—food that will stick to your ribs, and make you and all those you cook for smile (then ask for more).

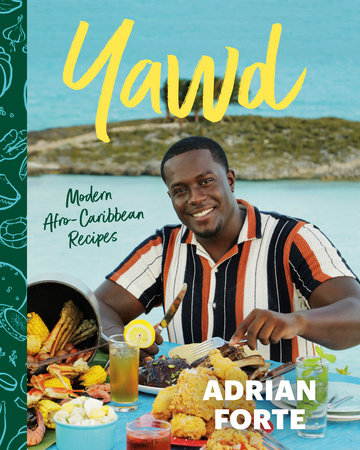

Deliciously Yours,

Adrian Forte

Copyright © 2022 by Adrian Forte. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.