The Farmhouse Culture StoryWhen I reflect back on all the factors leading up to 2008, it seems as though my entire life’s journey had been in preparation for Farmhouse Culture, and it all started with my grandparents’ farmhouse. Grandpa John, who owned the Guadalupe Mines in Los Gatos, California, and a small cattle ranch and walnut orchard in Gridley, California, was a largerthan-life Irishman who loved to eat (and drink), and my grandmother, Lillian, was happy to oblige him. My sister, mother, and I lived with my grandparents in Los Gatos for most of my childhood, but summers were spent at the ranch in Gridley. It was there in our old white farmhouse that I came to understand the connection between Grandpa John’s gardens and animals, and what landed on our plates. Both my grandparents cooked, but it was Grandpa who was the family preservationist. He canned everything, from dilly beans and tomatoes to grape jelly, and the entire family was required to pitch in. With every jar opened throughout the year, the memory of those raucous family gatherings, full of laughter, intense aromas, and sticky fingers, fortified our meals with deep satisfaction.

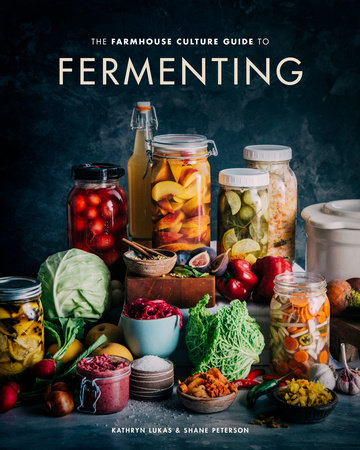

As I was tossing around names for my budding little sauerkraut company, I kept thinking back to my family’s farmhouse and my memories of how ingredients were lovingly transformed into healthful and delicious foods. Although my first products were sauerkrauts (because it was a familiar food for most Americans), I knew from the beginning that I wanted to eventually introduce many more traditional live-culture foods and beverages, and the name “Farmhouse Culture” provided the girth needed to expand. Yes, I thought, this would be a fine name for my new company, while honoring the care, lessons, and love my grandparents so generously shared with me. And it might even make up for breaking Grandpa John’s heart when I became a vegetarian.

It was my quirky Norwegian grandmother, Roxanne, who was convinced that my fiery teenage energy could be tamed with a vegetarian, macrobiotic diet. A free-spirited nonconformist, she was deeply distrustful of the corporate food system and in the 1960s had found her way to brown rice, whole-wheat bread, and tofu. She swore the new diet helped with her arthritis and might even save the world. It was in her wise care, and with her “hippie” foods, that I not only calmed down, but also fell in love with cooking. Grandma Roxanne taught me that knowing how to cook healthy foods was the ultimate form of rebellion, and that if one was going attempt to make the world a better place, a healthy body and a strong mind were absolute necessities. She lit the fire that still burns strong in my belly today.

Falling in love with a German and moving to Stuttgart, Germany, in my late twenties was another defining moment on the road to sauerkraut. At our restaurant, Das Augustenstüble, I learned to cook the regional Schwäbisch cuisine and to love canned sauerkraut—if it was properly prepared. Rinsed well; braised with apples, onions, and duck fat; and doused with wine, it was a huge improvement over the straight-out-of-the-can stuff Grandpa John served with hot dogs. But it wasn’t until a trip to a farm outside Stuttgart to refill our schnapps bucket for the restaurant that I discovered an even better version. Our visits had become an anticipated and delicious monthly ritual. The farmer, Herr Lutz, was a jolly and boisterous fellow and always eager to share the foods and drinks he and his wife worked so hard to grow and prepare. Normally there were things like apricots and plums and new flavors of schnapps, so I wasn’t totally prepared when Herr Lutz handed me a forkful of sauerkraut from a large wooden barrel. Still assuming that straight sauerkraut tasted like the canned kraut I was familiar with, I was hesitant, but of course I couldn’t refuse. I inhaled deeply and prepared for the onslaught of that intense salty sourness I had come to expect. But instead, I experienced a mild, pleasing tanginess and a slight herbaceousness, followed by just a hint of vegetal sweetness. The briny finish brought all the flavors together into a gorgeous and harmonious taste. This was something entirely different than canned sauerkraut, and I was immediately smitten. Herr Lutz provided me with a little history and a quick kraut how-to lesson, but it wasn’t until many years later in Santa Cruz that I actually made my first batch of sauerkraut.

I returned home to California in 1998, single and heartbroken. Over the next few years I worked in hospitality management, but eventually became restless. After so many years working with mostly Northern European haute cuisine, I had also become bored—I was itching to travel, to learn about new foods, and to cook again. Fascinated with vegan, raw, and traditional folk preparation techniques, I was also feeling nostalgic for the healthier foods from my grandmother’s kitchen, and in 2004, the Natural Chef Training Program at Bauman College in Santa Cruz seemed like a great place to start my journey back to cooking.

While there, I learned for the first time about digestive health. Donna Gate’s book

The Body Ecology Diet was required reading. One of the earliest nutritionists to use the terms

leaky gut and

inner ecosystem, her protocol to rid the digestive system of gut-disrupting candida yeast included ½ cup of raw cultured vegetables per day. In Germany, it was generally assumed that sauerkraut was healthy, and I noticed that the Germans drank the brine when they were hungover, but I’d never thought of it as a “health food.” In my world, sauerkraut had simply been an excellent culinary ingredient and condiment. I was intrigued, and could hardly contain my enthusiasm the day we made our first batch. We massaged salt into chopped cabbage, tucked it into a small fermenting crock, and waited. Over the next few days, the crock literally came alive with sounds and smells. We could it hear it gurgling and burping as we worked on other projects in the kitchen, and the sulfurous aroma intensified by the day. By the time we peeked inside, a couple of weeks later, the bubbling had subsided and a sweet, earthy aroma greeted us. Our instructor plunged her gloved hand into the crock and pulled out a mass of glossy cabbage shreds for us to sample. In a split second I was blasted back to Herr Lutz’s cellar, tasting that first revelatory bite of fresh kraut, and I was hooked.

At the time, Sandor Ellix Katz’s

Wild Fermentation was the go-to book for novice fermenters, but within the first few pages, I realized that it was much more than a fermentation manual: it was also a treatise on how to reclaim our food system and our health, and it spoke to something deep inside my soul. Right alongside my desire to learn a new food craft was a deepening frustration with the American food system. After experiencing the joy of regionally specific foods made by multigenerational food artisans in Europe, American cuisine felt shallow to me. Restaurant food, at the time mostly served up by chains, tasted the same whether you were in Boston or San Francisco, and much of the food found at grocery stores was overprocessed and filled with unpronounceable ingredients. Obesity was climbing at an alarming rate, and nutritionists were calling for bland lowfat diets to counter the trend. None of this felt right to me. I was drawn to the rich cultural history of traditional foods, and if rebelling against these strange new American food norms was a road map to a better world, then I was in. I know Grandma Roxanne would have approved.

I dug into Katz’s book with a religious fervor and discovered a hidden world of microbes that miraculously transformed ordinary ingredients, like cabbage, into superfoods. Sauerkraut was just the beginning. Crocks of pungent kimchi and chunky misos took over the closet in my spare room, and my counters were crowded with half-gallon jars of kombucha, kvass, and water kefir. My home felt alive with the sound of bubbling and the unfamiliar aromas, and I felt like a painter who had suddenly discovered a whole new spectrum of colors. As each new flavor emerged, I began imagining how it would taste paired with various ingredients and where it would best fit into a meal. Once I was comfortable with a basic formula, I would start tinkering with new ingredients, fermentation times, and temperatures just to see what was possible. There were plenty of slimy, skunky disasters, but there were also triumphs, and as my repertoire of recipes grew, I realized that I had found something more than a new craft: I had found my calling.

In a small cabin that overlooked a pond just outside Yosemite in Groveland, California, Farmhouse Culture was born. An opportunity to escape the bustle of the Bay Area for a few months had come up and the break afforded me the time and space I needed to dream and think my new business idea into life. The community was enthusiastically supportive, and soon I had hatched a plan with my new friends, farmers Christine and Eric Taylor, to turn their cabbage into sauerkraut for their CSA box. Our landlords, Ellie and Patricia (who were also our neighbors), offered their kitchen and cool basement for those very first batches of sauerkraut.

Copyright © 2019 by Kathryn Lukas and Shane Peterson. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.