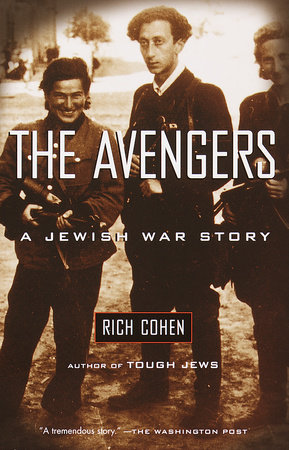

IntroductionIt is like no Holocaust story I have ever heard. There are no cattle cars in it, and no concentration camps. It takes place in underground hideouts and forest clearings, and in the ruins of German cities after the Second World War.

I first heard the story in 1977, when my family visited Israel, a trip partly chronicled in the photo album my mother put together when we returned to our house in suburban Chicago. The pictures show a smiling family backed by the usual landmarks: Western Wall, Dead Sea, Masada. I was ten years old. My brother was fifteen. In many photographs, he wears black, sun-absorbing concert T-shirts. In one, he makes a muscle. My sister, who would soon turn eighteen, looks bored, like every minute on this trip is another party missed. There is a shot of my father leaning on an Israeli tank, looking into the distance, as if scanning for Babylonians. My mother was taking the pictures, or else holding her hands over her face so no pictures of her could be taken. When it comes to photos, my mom is a classic case of dish-it-out-but-can't-take-it. Viewed together, these pictures record a middle-class Jewish pilgrimage, a family rite, Christmas in the Holy Land: kids squinting through the glare, searching out a lost connection, a link to a homeland that, after all that air travel, feels like just another country.

If you want to know about the rest of our vacation, those moments when the camera stayed in the bag, feuds, quarrels, threats and fits, you must dig deeper, beneath the old diplomas and hockey-mom patches, to the frayed pages of

The Cohen Daily News, a newspaper edited and published (by me) during the three weeks we spent in Israel. The paper, which was not really a daily, was handwritten on yellow sheets torn from my father's legal pads. Held together by a clip, the paper was passed from family member to family member. The stories, printed under smudged headlines, set down even the most scandalous rumors. Below my brother's byline ran a piece about my parents: "Herb and Ellen Fool Around." The article talked of a gleam in my dad's eye, of noises on the other side of a wall, of disheveled hair, of laughter. "Ellen was seen under the covers wearing a big smile," the story read. "Talk has it, that was all she was wearing."

Reviews ran in the back of the paper, including my dad's musings on a restaurant in Haifa where every dish was stuffed. "Not only is the food filling," he wrote. "It is stuffing." The last issue of

The Cohen Daily News, published as my parents packed, tells of a trip we made to a kibbutz north of Tel Aviv, a visit with relatives once thought lost in the Holocaust. In just a few paragraphs of my sister's blocky print, the story recalls the most important evening of our vacation, our first meeting with the Avengers, veteran fighters who slogged out World War II in the gloomy forests of Eastern Europe, later fought for Bible-bleached Middle Eastern wastes, and were the kind of people who inspired Joseph Goebbels to write in his diary: "One sees what the Jews can do when they are armed." In a dozen sentences, my sister set down the moment that fused the lost connection and made the homeland feel like home -- an electric moment that lurks just beyond the photos in my mother's album.

We drove to the kibbutz by rental car. The directions given to us by the man at the hotel were useless. Israelis -- who knows why -- give directions that are both clipped and broad, like every place is the same place, like any street gets you there: only a fool can miss it. "OK, you come out on the road and you are going," the man said, waving a hand. "You are going and going and going all the time. You are seeing a bridge but you are not going there because you are still going all the time. Then you see a tree, a building, and there you are."

We took a map. I had it on my knees. On family trips, I was the navigator. I was fascinated by maps. This one showed a sliver of land along the sea. Brown, blue. The names of the towns were familiar from religious school: Yafo, Jericho, Beersheba. Looking at the map, I began to sense just how abbreviated Israel is. It seemed the map was actual size. Picking out a town, I would say, "We should be in Netanya in two hours." And just as I was saying this, my father would gear down and say, "Here is Netanya."

We turned onto a road that ran through open fields. Little cars would dart up behind us flashing their lights. You could see them in the rearview mirror. Rolling down his window, my father waved them on. And off they would drive, bounding ahead, trailed by dust. We were going to see Ruzka Korczak; we had been sent by my grandmother. In 1920, my grandmother emigrated to New York from a small town in Poland, where she had nine siblings and an infant niece, the daughter of her oldest brother. Though my grandmother was to be just the first of the children to make the trip, the family ran out of money. And the seasons changed. And the politicians fell. And the War started. Several years after Nazi Germany collapsed, my grandmother got a letter from a woman named Sara, who came from her town in Poland. Sara now lived in Israel, where she searched for survivors, trying to put them back together with lost family. She met ships, studied dockets, interviewed passengers. Early in our vacation, we had lunch with Sara. Even if she had something of interest to say, I missed it. Her husband was named Shlomo; I could not move much beyond that.

In her letter, Sara told my grandmother that almost every Jew in their town had been killed. And yet a member of my grandmother's family had survived -- the niece. For much of the War, this niece had fought as a partisan in the forest. She was now settled on a kibbutz north of Tel Aviv. "Do you remember your niece?" wrote Sara.

"You are her only family. Her name is Ruzka."

The road climbed up a hill. Looking back, I could see the flat brown country below. It was blurry in the dust. We turned onto a bumpy trail. Fields rolled into the distance. The crops were so green they hurt my eyes. The air smelled like Illinois when the farmers sell their vegetables in town. We went around a bend, and there was Ruzka. I had heard stories about her, things she had done in the War. I had expectations. What I got instead was a slight, smiling, gray-haired Jewish woman not so different from my Grandma Esther, who was just then passing her golden years in a retirement complex in North Miami Beach.

When we stepped from the car, Ruzka gave each of us a hug, as if we had met many times before. She had the rugged face of a farm worker -- a dramatic backdrop for her eyes, which were warm and youthful. She asked us many questions and seemed to savor each answer, listening as fully as most people talk. As we followed her along the road, she pointed out buildings: "That is the dining hall," she said. "That is where the children live. That is where we keep the guns." In the distance, we could see children, cattle, goats. The kibbutz is a collective, a socialist settlement where you might work in the fields or pick fruit or milk cows. Spotting any cow, a local can say, "That is my cow." The few kibbutzim that still survive are hold-overs, relics from the pioneer days, when such one-for-all communities seemed the best way of coping with scorching summers and marauding neighbors. Looking to the eastern horizon, where the fields turned brown, Ruzka said, "Before we fought the Six Day War in '67, the other side of those fields was Jordan."

Ruzka led us to a white house with a red roof. The windows blazed with light. Inside, the walls were lined with paintings and books. Avi, whom Ruzka married after the War, a handsome, fair-skinned man with white hair and brilliant blue eyes, smiled and said hello. Since emigrating to Palestine in the thirties, Avi had spent much of his life trying to recapture the culture of his youth, the music and literature and food of Austria. "Avi, what are you doing?" asked Ruzka.

He was picking at the tray Ruzka had set out: fruit and vegetables.

"Darling, Ruzka, tell me, why no sausage?"

Ruzka smiled at Avi, and then fixed a plate for each of us.

There was a knock on the door. Then another. The floorboards creaked. The house filled with the smiles and guffaws of old Jews. "This is Abba Kovner," said Ruzka. I had been told Kovner was a poet, that he had won the biggest awards a writer in Israel can win, that soldiers carried his books to war. He looked like no one I had ever seen, a lost Old World prophet. His shoulders were hunched. His body was steely slender, a piece of modern sculpture, edges and angles. His eyes shone with a dark, secretive melancholy. In any picture, his face recedes, more still and somber than the surrounding hills. At his side, never beyond whispering distance, was his wife, Vitka. She was long-limbed, with dark hair and big eyes. Her face was plain until she smiled and her smile remade her face and then her smile was gone and her face fell again into the blank gaze she must have worn as a girl in Eastern Europe.

Abba, Ruzka, Vitka -- this was not an ordinary relationship, not the conventional idea of a married couple crossing the fence to visit a neighbor. These people had met over thirty years before, in the cramped streets of Vilna, the capital of Lithuania -- kids caught in the second act of World War II. Some people have tried to cast their relationship in terms of a traditional love triangle. They say Ruzka and Vitka were in love with Abba, or Abba and Ruzka were in love with Vitka, or Vitka and Abba were in love with Ruzka. In truth, all were in love with all. They finished one another's sentences, read one another's thoughts. The things they endured and survived bound them in ways hard for anyone living today to imagine.

For the most part, they did not like to talk about the past, or about their own exploits. They wanted to know about America, or Chicago, or, in my case, the rigors of fifth grade. Only slowly, often from the mouths of other people, did we learn of the underground army they formed in Europe, of the battles they fought with the Germans, of how they escaped Vilna moments before the Jewish ghetto was destroyed. There were also stories of the forest, where they lived and fought for a year, blowing up enemy trains and transports. The forest is where they spent their last days in Europe. It is where the old life came to an end. And it's where the new life began -- where Israel was born. The story of Abba, Ruzka and Vitka is, after all, a Middle Eastern story. In the woods they were already fighting as Israelis. The courage and grit they found in the trees was the most important thing they would bring to Palestine. The forest is also where they devised the outlandish plots they would carry out in the chaotic days after the War -- plots whereby they visited a measure of vengeance on the men who had killed their families. As they spoke, the sky outside filled with stars. Constellations wheeled. Yellow light glowed in the windows and the room seemed to fall into the past, to the cities and swamps of their youth.

As I grew up, I spoke with Ruzka and Abba and Vitka numerous times, on trips we took every few years to Israel and on their visits to the United States. In my memory, their story plays out before a shifting backdrop -- houses by the sea, suburban lawns, crowded restaurants. I once met Abba in Tel Aviv at the Diaspora Museum, which he had conceived and designed. The museum was built to tell the story not just of the slaughter of the Holocaust, but of the years of Jewish life that had come before the slaughter. His hair was long and gray and he wore chinos and kept his hands in his pockets. He led me through halls of documents and photographs. In one room, he stood before a detailed model of the Great Synagogue of Vilna, a graceful network of arches and supports. "How can you know what we lost," said Abba, "if you don't know what we had."

I usually met Abba, Ruzka and Vitka in their homes on the kibbutz, in rooms crowded with books and music and paintings. Abba and Vitka's son, Michael, is a painter, and often I sat looking at his airy watercolors of houses in the Negev desert. As Abba or Ruzka spoke, doors opened and members of the old crowd wandered in, smiling and laughing, filling in the story. To an American, these people seemed an exotic hybrid -- rugged intellectuals, fighters schooled only by their experience and curiosity. When Ruzka listened, she let her hands fall to her sides, opened her eyes and drank in every word. I often spoke with her as we walked the narrow lanes of the kibbutz, past houses glowing with life, insects underfoot. She held her hands behind her back and talked in a soft voice.

Our visits to the kibbutz were mostly passed happily with our family, with Ruzka and her children -- who are my cousins -- Yehuda and Yonat and Ghadi, their spouses, and their children. Still, whenever I found a chance, I steered the conversation back to Europe, their lives before the war, how they survived, what they did when peace came. I suppose I was obsessed. To me, their story seemed to offer a view of history different from what I saw on television or read in books -- this was World War II as seen from the East, by those on the bottom, by Jews who, with nothing else to lose, decided to fight.

In 1998, I traveled to Israel to meet with Vitka and the other partisans -- those who were still alive, anyway -- who had fought with her during the War. By gathering the strands of the story, I hoped to set down a legacy that had been so carefully passed to me. I lived in a guest cottage on the kibbutz and spoke with Vitka each morning, or else she took me to some nearby kibbutz where other former comrades were living. If a person was unwilling to speak of the past, she would tell them I was a cousin of Ruzka's. They would look me over, smile and say, "Ruzka was wonderful. Let us speak in the garden."

Over a period of several weeks, these people told me in greater detail stories I already knew and also told me others I could never have imagined, stories they had never told anyone, the last great secrets of the War. When I asked Vitka why she had kept these things hidden, she frowned. Abba did not want these stories told, she explained. Israel was then living under a terrorist threat and Abba was afraid members of extremist groups might use his actions during the War as an excuse for their own behavior. Even more, he was afraid other Jews would not understand the life he had lived in Europe; removed from the context of war, his actions might seem brutal or cruel.

I asked Vitka why she had decided to tell the story now, and she talked about time and how things change. When Abba and Ruzka died, she realized that, if she did not tell their story, it might die with her.

One evening, on the kibbutz, Vitka led me into the fields, beyond the furthest porch light. A bird rose in the sky. Stars danced on the horizon. We reached a patch of manicured grass, each blade trembling in the evening breeze. Headstones were set in neat rows, dates of birth and death spanning the short history of the nation. On the edge of the cemetery, Vitka stood over two graves: Abba and Ruzka, buried just a few feet apart. To the other side of Abba, there was a third plot, an empty plot, which Vitka was careful not to step on. Vitka placed a small rock on each headstone, closed her eyes and said something under her breath. She looked at the ground, then back toward the kibbutz. "Come," she said. "Let's go home."

Copyright © 2001 by Rich Cohen. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.