IntroductionHow I became a cook is not a romantic story. I learned how to cook Puerto Rican food from my grandmother, Margarita Galindez Maisonet. Margarita was born in 1938 in the campo of Manatí, on the northern coast of the island not too far from Hacienda La Esperanza, a former sugarcane plantation. When Margarita was nine years old and in the third grade, she was sent to live with her Titi Emilia. That was the end of Margarita’s formal education. That was also the end of seeing her biological mother for several decades. Margarita went to work as a “domestic” during a time when people didn’t have to apologize for deep-frying their foods, when it was a way of life. There would be no passing down of heirloom cookbooks (I don’t think my grandma ever owned a cookbook), words of encouragement, or time to enjoy a childhood. By the time that Margarita was fourteen years old, she was already pregnant with the first of her seven children, Carmen, my mother. Margarita, Carmen, and I became cooks out of economic necessity. We did not have the privilege of cooking for pleasure or joy. Our story is one of generational poverty and trauma with glimpses of pride and laughter, all of which have been the catalysts of ample good food in my life.

My own days begin with only the sound of my feet shuffling through dawn’s sleepy light. I turn on the stove. Shuffle to the sink; the faucet knob squeaks and the aerator spits. My black pinky toenail and I wait impatiently for the spouted Le Creuset pot to fill with water. Shuffle to put the pot on the burner. The pour-over cone goes on top of the coffee mug, the coffee filter into the pour-over cone, then the coffee grounds. In the meantime, I open all the windows in the front of the house to let the morning coolness seep through the mesh screens. By the time my shuffling feet make it back to the stove, the water is bubbling. I pour the water over the coffee grounds, and the conjured smell of foggy mountains in the interior of Puerto Rico fills my California kitchen. The water sinks into and penetrates the cone, sending the dominion brew into the cup below. A flourish of cream ends my ceremony. This entire process mirrors my late grandmother’s morning routine, although her pot of choice was a small aluminum Farberware made in the Bronx, and her pour-over cone was a colador. She began every waking morning with this routine, a necessary moment of meditation and coffee to galvanize her weary body into the next step—starting the daily meals, which always consisted of rice and beans.

Many of the old Puerto Rican recipes aren’t quick and easy, which might be one of the reasons that the food of the island hasn’t exactly taken off in the land that sits mere hours away. Another reason is probably because people don’t understand the cuisine. Hell, most people don’t understand us! “How can brothers and sisters from the same two parents range in color from white to Black?” they ask. Colonialism. There are white Puerto Ricans getting radical and surfing in Rincón with sun-bleached blond hair, and Black Puerto Ricans with afros creating arts and crafts in Loíza. And everything in between. And our food reflects that diversity. We know how much people love to have things simplified so it all fits neatly into a little box. The truth is, Puerto Rican cuisine shares a lot in common with the cuisines of Hawai‘i, Guam, and the Philippines—all the places that got f***ed by Spanish and United States colonialism. To most, Puerto Rico is just a pit stop on their boat cruise to the Bahamas. “I loved Old San Juan and mofongo” is the common response I hear when I tell someone I’m Puerto Rican. To Puerto Ricans, Puerto Rico represents a constant battle for land and a broad understanding of our identity.

When my family first came to the States and my mother was enrolled in elementary school, she didn’t speak any English. During the country’s Cold War–era security push, it became necessary to read and write English well, which meant that racist policies, such as the “No Spanish” rule, lingered in the newly desegregated schools. And so, my mother just didn’t speak. It was a decision that would mold her personality to this day (and the reason that I don’t speak Spanish). A more confrontational person might have rebelled and fought. That’s not my mother’s way. How could she have been confrontational at five years old? Well, ask my mom what happened when my kindergarten teacher wouldn’t let me wash my hands after I went to the bathroom. All hell broke loose! I suppose because of my mother’s inability to speak out, she made sure that I was the opposite of her in that way.

Anyway, during Margarita’s (my nana’s) first years in the States, she spent her mornings in the fields picking produce, spent her evenings in the kitchen cooking for her husband and children, and spent her nights procreating more children. Every day. Routines and rotations of Puerto Rican recipes passed down to her from her aunt, who raised her, and her biological mother. “The mama who gave birth to me, or the mama who raised me?” she’d always clarify when asked about her mother. By the time that I arrived on this spinning marble of malachite and lapis lazuli, Nana already had a few recipes in the rotation that had been absorbed, digested, and regurgitated as “American”—spaghetti, oven barbecue, hamburgers, meatloaf, and pancakes the size of dinner plates. But she mostly made Puerto Rican food. And, for Nana, as someone who was a part of what would eventually become the 5.5 million Puerto Ricans living Stateside, mostly on the East Coast and in Florida, being on the West Coast always emphasized a pivotal issue: No one seems to know anything about Puerto Rican food. Sometimes, not even Puerto Ricans.

Puerto Ricans are quick to argue about the roots and regulations of what Puerto Rican food is. Honestly, they just love to argue. (Guilty.) There are Puerto Ricans who don’t know shit about their own cuisine. No shade. That tends to happen when you believe it’s your birthright; you take it for granted. Sometimes it feels like, somewhere along the line, Puerto Ricans lost their way. And with it, their food. With colonization, that isn’t entirely unintentional. There can be several arguments against why there’s no emphasis on the beauty of Puerto Rican cuisine. Puerto Ricans don’t tend to be cerebral about their food but rather emotional.

More than 80 percent of food consumed in Puerto Rico is imported. The costs of importing products, especially food, make them more expensive than if they were produced locally. Most of the time, the food is not even good quality because it has lost its freshness during the long shipping to the island! And don’t let it be hurricane season while all this is happening. United States citizens made such a fuss over the “pandemic pantry.” Puerto Ricans’ pantries are basically in a perpetual state of survival mode. The pandemic pantry is a lot of folks’ everyday pantry. And all the inequity of the United States’ industrial cookery culture has really left its mark on Puerto Rican cooking. There’s not a single word that I could use to define Puerto Rican cuisine. If I were forced to pick one, I’d choose sofrito. This herb paste made of culantro, cilantro, tomatoes, garlic, onion, and chiles or other peppers is the bedrock of our cuisine, which is a straightforward, proletariat proposition—something flavorful, hot, and filling to maintain your strength while you work.

We are Taino, Spanish, and African. The peaceful Taino were not native to the Caribbean; much like their enemies, the cannibalistic Caribs, they migrated to the Antilles from South America. Lots of Taino culture still runs through our veins and our vocabulary—words such as barbecue, hammock, canoe, and iguana. The Taino presence is still felt on the island of Borinquen. The Taino called the island Borinquen (land of the brave lord), which is why Puerto Ricans call themselves Boricuas to this day. The Spanish renamed it Porto Rico. While the legend of the Jibaro farmer might be one of folklore, the Taino influence lives on.

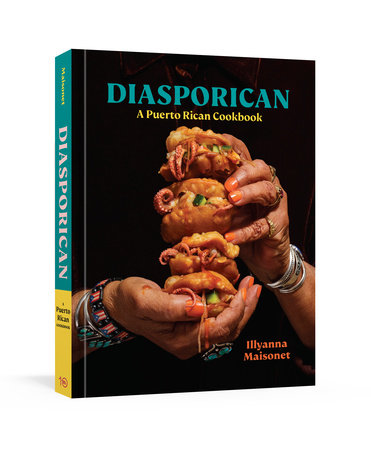

Copyright © 2022 by Illyanna Maisonet; foreword by Michael W. Twitty; photographs by Dan Liberti and Erika P. Rodriguez. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.